Introduction

The opioid epidemic is a public health crisis affecting patient populations across multiple medical specialties.1 In 2018 alone, a reported estimate of 10 million people misused opioid drugs, and over two million were diagnosed with opioid use disorder.2 By 2021, opioid-related deaths surpassed over 100,000 deaths annually and became the leading cause of death among young adults, surpassing car accidents.3 The cause of the opioid crisis is multi-factorial, but combatting it requires both public awareness of the harm of opioids and physician employment of opioid stewardship.4,5 At the forefront of prescribers are orthopedic surgeons, representing the third highest opioid prescriber specialty, falling behind family practitioners and internists, and accounting for 7.7% of total prescribed opioids.6 Total joint arthroplasty (TJA) represents a large portion of orthopedic surgeries performed annually, routinely relying on opioids for postoperative pain management.7 Despite generalized efforts aimed at institutions to develop opioid prescription guidelines for common surgeries such as TJA, they have not been widely adopted.8–11

Academic centers have been at the forefront of pioneering evidenced-based opioid prescribing following TJA surgeries. Recognizing their crucial role in shaping clinical practices, these institutions have re-evaluated their pain management protocols to strike a balance between adequate pain relief and minimizing opioid dependence.8,11 Despite this pendulum change towards a more conservative approach in opioid prescribing, there is little data, to our knowledge, that quantifies prescribing pattern trends. Understanding opioid administration patterns following TJA can better inform post-operative pain management prescribing, reduce opioid reliance in post-operative care, and lead to the development of new guidelines for management that could mitigate the risk of opioid misuse. Therefore, this study aims to characterize opioid administration patterns following primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA) across multiple healthcare institutions and healthcare settings to better understand trends in recent years.

Methods

The institutional review board was not required as the data analyzed was drawn from Avalon.ai (Philadelphia, PA), a third-party agent, with all patient information provided de-identified by respective institutions. Avalon.ai is a value-based data analytics company that provides healthcare-related data for payors, providers, and medical device/pharma companies.12

A retrospective analysis was performed utilizing de-identified patient data culled by Avalon.ai, consisting of 3 geographically diverse institutions: Institution #1 in New York state (representing the Northeast) between 2020 to 2022, Institution #2 in Iowa (representing the Midwest) between 2018 to 2022, and Institution #3 in Louisiana (representing the South) between 2021 to 2022. The data was screened for patients undergoing TKA and THA (n=4,472). Patient cohorts were determined by healthcare institutions: Institution #1 (n=669), Institution #2 (n=1,993), and Institution #3 (n=1,810). Patient cohorts were stratified by procedure type: TKA (n=2,913) and THA (n=1,571) and procedure setting: inpatient TKA (n=211), inpatient THA (n=273), outpatient TKA (n=2,705), and outpatient THA (n=1,300). This study did not utilize patient-identifiable information and was subsequently deemed Internal Review Board (IRB) exempt.

The primary outcome was the administration of opioids within the healthcare setting immediately following respective surgeries. Opioid values were defined as morphine milligram equivalents (MME), representing the potency of the opioid dose relative to morphine. Analyses were performed by surgery and healthcare institutions to determine MME trends.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed to compare average MME across years, between procedure type, setting, and healthcare institution. Differences between categorical exposure and continuous outcome measures were compared using 2-tailed z-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) test as appropriate. All P-values presented were 2-sided, with a P-value of ≤.05 considered statistically significant. Tukey HSD (honest significant difference) post hoc analyses were conducted using ANOVA testing to indicate significant differences between groups.

Results

Opioid administration was analyzed using the TJA surgical procedure type, surgery setting, and center.

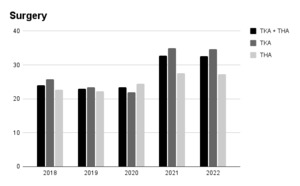

4,472 TJA surgeries were performed between 2018 and 2022 [Table 1]. When combining institutions, there was a significant increase in average MME for TJA from 24 ± 18 in 2018 (n=421) to 33 ± 28 in 2022 (n=1233) (P <.0001) with statistical difference between annual groups (P <.0001) [Figure 1].

Opioid Administration by Procedure Type

There was a significant difference in average MME following TKA (P<.0001) among annual groups, with a significant increase from 26 ± 19 in 2018 to 35 ± 27 in 2022 (P=0.0002). THA had a significant difference in average MME across annual groups (P=0.03), with an insignificant increase from 23 ± 16 in 2018 to 27 ± 31 in 2022 (P=0.316). TKA had a significantly higher average MME when compared to THA in 2021 (35 ± 29 vs 28 ± 29, P<.0001) and 2022 (35 ± 27 vs 27 ± 31, P=0.0004).

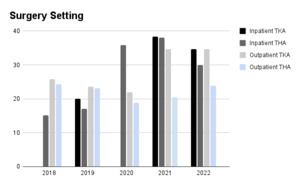

Opioid Administration by Surgery Setting

When combined for healthcare institutions, there was a significant difference in average MME following inpatient TKA (P=0.0003) across annual groups, with a significant increase from 31 ± 24 in 2020 to 35 ± 29 in 2022 (P=0.0172). [Figure 2] Inpatient THA had significant differences among annual groups for average MME (P=0.0188), with an insignificant increase from 15 ± 22 in 2018 to 30 ± 38 in 2022 (P=0.4).

There was a significant difference between annual groups for outpatient TKA (P<.0001), with a significant increase from 30 ± 38 in 2018 to 35 ± 26 in 2022 (P=0.0002). There was a significant difference between annual groups for outpatient THA (P<.0001), with an insignificant reduction from 24 ± 14 in 2018 to 24 ± 14 in 2022 (P=0.9980).

In 2021, inpatient surgeries had a significantly higher average MME of 38 ± 33 compared to outpatient surgeries (31 ± 28, p=0.0004). There was an insignificant difference in average MME in 2022 (P=0.9332)

Opioid Administration by Institution

There were significant differences in average MME administered when combining surgeries and surgery settings amongst the healthcare institutions in 2021 and 2022 (P<.0001). [Table 2]

Discussion

This study yielded some patterns in opioid administration following TJA, including an overall increasing MME trend, higher MME post-TKA, and higher MME following inpatient TJA, with variation in MME amongst healthcare institutions in recent years. TJA is commonly associated with high opioid administration postoperatively.7,13 Due to the evolution and subsequent high success rates of modern TJA, the past several decades have dramatically increased volume, making it the most commonly performed orthopedic surgery.14 Based on recent volume counts, it is estimated that TKA and THA will increase by 469% and 659%, respectively, by 2060.15 As such, it is pertinent to understand administration patterns related to TJA to curtail inappropriate dispensing of these drugs. The focus within the literature has shifted to reducing opioid prescriptions following TJA.7,13,16

When comparing administration patterns following TKA and THA, there was higher opioid consumption for TKA in recent years. Numerous retrospective studies found similar findings, with more prescriptions and higher utilization of opioid medication by TKA patients and a higher likelihood of developing chronic opioid use after surgery.16,17 In a study examining opioid prescriptions following TJA in opioid-naive patients, TKA patients were prescribed 632 MME in contrast to THA patients receiving a mean of 416 MME.16 Goesling et al. found 8.2% and 4.3% of opioid-naive patients continued consuming opioids six months post-TKA and THA, respectively. In contrast, 53% of TKA and 35% of THA patients who reported opioid use on the day of surgery continued to use opioids at six months.17 Increased opioid utilization post-TKA has been attributed to the painful rehabilitation occurring during the acute post-surgery period, which is essential for enhanced recovery.18 Roebke et al. found that patients undergoing TKA had higher daily inpatient opioid use, a higher total 90-day number of opioids prescribed, and a higher likelihood of requesting an opioid refill post-discharge.19 In a study examining opioid use during hospitalization following TKA, there was a reduction in daily average MME from 2016 to 2021 (43 ± 69 vs. 15 ± 29).20 In contrast, this study found an increase in MME from 2018 to 2022 following TKA (26 ± 19 vs. 35 ± 27).

Over-administration of opioids following inpatient TJA has been studied, with rates of 34% following TKA and 140% following THA.13 Varady et al. found outpatient TJA to be associated with reduced opioid prescribing when compared to inpatient TJA (79% vs 88%). Among the patients receiving opioids, there was no significant difference in MME when comparing inpatient to outpatient. However, inpatient TJA patients were more likely to continue taking opioids after 90 days postoperatively.21 Similar patterns of opioid administration were noted within this study, as average opioid consumption was significantly higher for inpatient TJA than outpatient in 2021 when combined for healthcare institutions, and there was no difference in 2022. This trend is likely attributable to increased focus on multimodal protocols for pain management in the outpatient setting.22 Similar increased attention to multimodal analgesia in the inpatient setting may further reduce opioid overprescribing following inpatient TJA.23 Medical optimization through a multidisciplinary approach has allowed TJA to be more feasible for younger patients in which quicker recovery times are expected, necessitating appropriate pain management postoperatively in the outpatient setting.24

In 2021 and 2022, there was a significant difference in average MME when comparing individual healthcare institutions (p<.0001). Geographic variation in institutions has been associated with varying opioid prescription rates. However, definitive conclusions of over or under-prescribing were unable to be drawn.25 In efforts to remedy such differences, the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) has called for standardization of opioid prescribing practices across institutions. In a sample orthopedic department opioid safety strategy, the AAOS suggested prescription of no more than 60 opioid pills of a maximum of 5 mg of oxycodone (or equivalent) per pill, a single refill with no more than 30 pills, and discontinuation of opioids within one month of surgery following major orthopedic surgery including TJA.26 However, the AAOS does not support specific guidelines to be utilized across all patient populations as a replacement for clinical judgment or individualized patient-centered care.27

Recent evidence-based opioid prescription guidelines by D’amore et al. recommend a combination of non-opioid analgesia consisting of acetaminophen, pregabalin, and celecoxib, in addition to tramadol 50 mg per oral (PO) every 6 hours as needed (PRN) for moderate pain and oxycodone 5-10 mg PO every 4 hours PRN for severe pain following THA.28 Similar recommendations were given post-TKA with ketorolac substituting celecoxib. Upon discharge, clinicians are recommended to prescribe a combination of acetaminophen (1g/240 pills), celecoxib (15mg/30 pills), and pregabalin (75mg/60 pills) following THA, with the addition of tramadol (50 mg/15 pills) and oxycodone (5-10mg/15 pills) for breakthrough pain following TKA at the lowest feasible dose, duration, and quantity. Thorough patient evaluation for risk of opioid abuse should be considered prior to opioid prescription in addition to patient counseling. These recommendations are in addition to periarticular injections done prior to surgery. Additional studies found differences in opioid administration guidelines across different healthcare organizations.29–31 Currently, all states require education on opioid administration, although specific requirements vary by state.32 As such, requirements can vary from single courses to more extensive educational programs requiring multiple hours throughout the year.

Multimodal analgesic regimens have been shown to provide adequate pain relief in substitution of opioids following TJA.33 Overall, the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, NSAIDs, spinal analgesia, peripheral nerve blocks, and intra-articular injections have resulted in improved VAS pain scores when compared to opioids alone.33 Peripheral nerve blocks following TJA have been shown to reduce consumption of patient-controlled opioid analgesia with faster time to rehabilitation.34,35 Epidural analgesia has been associated with improved pain control when compared to patient-controlled analgesia with morphine in the inpatient setting with a reduction of duration of postoperative rehabilitation.11,13 NSAIDs and their related cycloxygenase type-2 (COX-2) inhibitors have been found to significantly reduce opioid consumption with a decrease in VAS pain scores.36,37 Newer multimodal pathways are increasingly gaining popularity as safer and more effective alternatives to traditional opioid-heavy regimens and should be regarded as the initial option for management.28,38,39 Preoperative opioid education has been shown to significantly reduce opioid consumption postoperatively when compared to patients not receiving opioid education with no adverse effects on pain experience.40 Despite the evidence supporting multimodal analgesia in TJA, barriers to its implementation have been identified. These include provider lack of familiarity with evidence supporting the use of multimodal analgesia and lack of knowledge on multimodal agents.41

With the rise in orthopedic procedures over the years, the associated opioid prescriptions have also seen an upsurge. This, coupled with the chronic nature of pain associated with orthopedic conditions, creates a milieu ripe for prolonged opioid use and potential misuse.7,13 As the pendulum swings towards more judicious use of opioids, there is an increased emphasis on exploring multimodal analgesic methods that utilize non-opioid medications and alternative therapies to optimize postoperative pain control while minimizing opioid use and its associated complications. This approach not only offers the potential for improved pain management but also addresses the pressing public health concerns associated with opioid misuse and overdependence.22,23

This study has several limitations. The first is the unequal proportions of patient data provided by individual institutions and by surgery type and setting. Additionally, the data is not representative of follow-up visits, and therefore, we are unable to ascertain patient consumption of prescription opioids after discharge or lack of them. This study was not adjusted for potential confounding variables such as patient demographics or comorbidities. Future studies should aim for more comprehensive and longitudinal data to better understand the root causes of opioid administration patterns.

Conclusion

Opioid administration following TJA has increased in recent years with differences in average MME across individual healthcare institutions. Interventional efforts should continue to be made in reducing opioid administration following TKA and THA and standardizing prescribing guidelines across all healthcare settings to continue mitigating long-term use and abuse.

Declaration of conflict of interest

Dr. Ahmed Siddiqi is a board member and stock options in AZ Solution LLC, stock options in ROMTech, stock options and board member of Stabl.

Declaration of Funding

This study was supported by a grant from Pacira Bioscience (Tampa, FL) received by the Rothman Opioid Foundation, which organized this study.

Declaration of ethical approval for study

Not Required.

Declaration of informed consent

There is no information in the submitted manuscript that can be used to identify patients.