INTRODUCTION

Instability after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) is a serious complication that can be difficult to manage1,2 A recent multicenter study comprising over 6,000 patients across fifteen institutions showed a dislocation rate of 2.1% following RSA with risk factors including male sex, revision surgeries, lack of subscapularis repair, history of postoperative subluxation, cuff disease, and nonunion.3 Surgical factors associated with instability include component malposition, insufficient restoration of humeral length, inadequate soft tissue tension, liner wear, bony impingement, infection, and axillary nerve dysfunction.4 Effectively addressing instability requires a thorough understanding of the underlying cause.4 Numerous approaches for treating instability after RSA have been developed, each addressing various etiologies.4 However, despite these treatment options, instability can persist even after revision surgery.5

Tashjian et al. have described using a suture cerclage between the proximal humerus and scapula in patients with recurrently unstable RSA.5 This technique paper presents our modified glenoid-anchor cerclage technique, which is similar in principle but employs an all-suture-based suture anchor. This technique involves placing the suture anchor superiorly in the glenoid, above the glenosphere. One posterior suture limb is passed through a trans-osseous tunnel drilled from the postero-superior aspect of the greater tuberosity to the bicipital groove. In contrast, the other anterior suture limb is passed through the subscapularis [Figure 1]. Tying the posterior and anterior limbs to their corresponding ‘free sutures’ provides restraint against superior migration and anterior displacement, respectively. The result is a stable glenoid-anchor cerclage that is technically easy to perform and requires limited operative time.

INDICATIONS & CONTRAINDICATIONS

The primary indication for this cerclage glenoid anchor technique is instability following RSA. It is important to note that recurrent instability arises from complex, multifactorial causes, and revisions commonly involve corrections to the humeral components, baseplate, and glenosphere. Contributing factors such as soft tissue contracture, scarring, and impingement should also be addressed during revision to mitigate recurrent instability. Ensuring correct component alignment, optimal soft tissue tension, and eliminating mechanical impingement are essential before considering the internal brace technique. Patients identified preoperatively as high risk for dislocation in the primary setting may also benefit from a glenoid-anchor cerclage. Risk factors for instability following RSA that have been reported in the literature include but are not limited to proximal humerus fracture nonunion, rotator cuff disease, male sex, revision surgeries, presence of humeral spacers or a constrained polyethylene insert, subscapularis insufficiency, failure to tension soft tissues, and component impingement.2,3

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Surgical Preparation

-

All imaging studies are reviewed for instability, loosening, glenoid and humeral bone loss, and humeral length. RSA instability can be classified through the following4:

a. Loss of compression due to undersized implants, loss of deltoid contour, loss of humeral height, subscapularis insufficiency, acromial or scapular fracture, or deltoid dysfunction.

b. Loss of containment due to mechanical failure or altered humeral socket depth to radius ratio

c. Impingement due to soft tissue or bony impingement, prosthetic malalignment, or body habitus

-

The patient is placed in a secured beach chair position. After prepping and draping, the operative arm is positioned off the side of the bed with an arm holder device or an assistant to allow for shoulder movement in adduction and hyperextension.

Surgical Equipment

-

All-Suture Anchor

-

Disposable Kit +Obturator

-

2mm drill bit + soft tissue protector

-

Suture Retriever

-

Taper Point free Mayo needle

Surgical Steps

-

The treating surgeon can use their preferred approach and implants for shoulder arthroplasty.

-

Suture Anchor Placement

-

Following placement of the baseplate in the desired position, the all-suture anchor is placed on the superior aspect of the glenoid, specifically at the 12 o’clock position, in preparation for employing the glenoid-anchor cerclage technique at the end of RSA. [Figure 2a]

-

Separate the four sutures from the anchor into two separate limbs consisting of 2 sutures each.

-

Temporarily place one set of sutures anteriorly and the other set posteriorly around the humerus.

-

-

Glenosphere Selection and Placement

-

Select the appropriate glenosphere based on the anatomical and surgical requirements.

-

Carefully impact the glenosphere into its designated position on the glenoid, avoiding entrapment of the free sutures from the suture anchor under the glenosphere.

-

-

Humeral Preparation and Trial:

- After securing the glenosphere, humeral components can be trialed, ensuring the sutures from the anchor are pulled out of the surgical field to avoid undesired strain on the anchor.

-

Preparation for Glenoid-Anchor Cerclage:

-

Drill a transosseous tunnel anterior to posterior through the greater tuberosity using a 2.0 mm drill bit with a soft tissue protector. Start drilling in the bicipital groove and exit through the postero-superior aspect of the greater tuberosity, lateral to the humeral component. [Figure 2b]

-

Pass the suture passer into the trans-osseous tunnel from anterior to posterior using the suture passer, and pass one of the two sutures from the posterior limb through the trans-osseous tunnel from posterior to anterior.

-

-

Final Implant Placement and Reduction:

- After securing the sutures, the final humeral component and liner can be implanted, confirming the sutures are not entrapped under the implant.

-

Glenoid-Anchor Cerclage Placement:

-

Take one suture from the anteriorly based limb and pass the one suture through some of the remaining subscapularis tissue using a free Mayo needle with a tapered tip. [Figure 2c]

-

Once the sutures have been passed, tie each to their corresponding ‘free’ suture to complete the cerclage. Start with the posterior suture limbs, hand-tie the sutures together, ensuring that the limb going through the trans-osseous tunnel is the post (to ensure that the knot lies flat on the humerus and not the glenoid). This loop will serve as a restraint to superior migration. [Figure 2d]

-

After securing the posterior limb, tie the sutures from the anterior limb similarly, using the suture coming out of the subscapularis as the post to ensure the knot lies flat on this tissue. This loop serves as a restraint to anterior displacement. [Figure 2e]

-

We recommend repairing any available subscapularis tissue back to the humerus using the surgeon’s preferred technique. Our method involves three suture tapes that are tied down using Nice knots.

-

-

Final Assessment:

- Conclude the procedure with a thorough assessment of the shoulder’s stability. Confirm that the shoulder appears stable throughout the arc of motion with no lateral shuck or excessive anterior gapping. While assessing range of motion, ensure that the sutures are not impinging or rubbing on the implant.

Postoperative Management

- All patients are treated with a standardized postoperative rehabilitation protocol, which involves a restricted shoulder range of motion in an immobilizer followed by a gradual and progressive range of motion. Patients are generally able to perform gentle daily activities two to six weeks after surgery.

We have included 2 cases below that have been treated with a glenoid-anchor cerclage for varying indications of instability and all who have shown successful and complication-free postoperative function and rehabilitation. A long-term outcome study is needed to confirm whether these patients have had successful outcomes.

Case 1

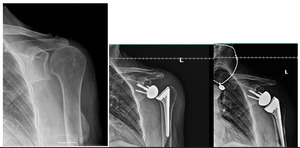

The first patient is a 78-year-old female who initially presented with severe rotator cuff arthropathy following a previous rotator cuff repair. The patient underwent a reverse shoulder arthroplasty procedure and subsequently sustained an atraumatic dislocation one month postoperatively with an anterosuperior translation of the humeral component relative to the glenoid. A revision procedure was then performed for the patient, which involved upsizing the tray to a +8 with a +4 semi-constrained polyethylene liner and increasing the glenosphere size from 32+4 mm to 36+4 mm. As per the described technique, a glenoid-anchor cerclage was also placed to provide additional stability to the construct. One year postoperatively, the patient remains stable with no evidence of complications associated with the glenoid-anchor cerclage. The patient has a forward elevation of 120 degrees and an external rotation of 10 degrees, with an American Shoulder and Elbow Score (ASES) and Single Assessment Numerical Evaluation (SANE) score of 60. The patient has also expressed a high level of satisfaction with the surgery. She has noticed some improvement over the past six months and is optimistic about further progress in the coming year. Her primary goal is to regain enough mobility to play golf again. [Figure 3]

Case 2

The second patient is a 76-year-old male who first presented with evidence of non-united proximal humerus fracture and posttraumatic arthritis. The patient was treated with RSA, which then dislocated one month following the initial procedure. X-ray imaging revealed a superolateral translation of the humeral construct consistent with complete dislocation. The patient underwent a revision arthroplasty procedure involving the placement and exchange of the 36+4 mm glenosphere with a 40+4 mm glenosphere, reconstruction of the greater tuberosity with humeral allograft, and placement of a glenoid anchor cerclage within the joint for added stability. At two years postoperatively, the construct remains stable, and patient-reported outcomes continue to be elevated, with a visual analog score (VAS) pain of 0 and a SANE score of 70.

Regarding range of motion measurements, the patient has 90 degrees of forward elevation, 40 degrees of external rotation, and the ability to internally rotate to the sacrum. The patient also presents free of complications associated with the glenoid-anchor cerclage. [Figure 4]

.

DISCUSSION

Instability following RSA is a serious complication with various etiologies.2,4 To address the different causes, various strategies have been developed for addressing this undesirable problem. Soft tissue tension can be improved by increasing glenosphere size, optimizing glenoid and humeral-based lateralization, or addressing the height of the humeral component.2,4 To reduce impingement, baseplate positioning can be optimized through more inferior placement, and impinging osteophytes can be removed.2 The use of constrained liners and repairing any remaining subscapularis tendon are other adjuncts that can also improve joint stability. Despite these interventions, outcomes of revisions after postoperative dislocations are inferior compared to primary arthroplasties.3,6,7 Recurrent instability and the need for additional revision surgery are also a significant concern. Cronin et al. reported that among 40 revisions for dislocations, 42.5% proceeded to sustain additional dislocations, 35% required an additional re-revision, and stability was never achieved in 14%.6 A large multicenter study including 6,621 RSA patients reported 22.2% for recurrent dislocation after revision surgery and 13% overall incidence of patients failing to achieve stability.3

Few alternatives remain for recurrent instability outside of salvage options such as resection arthroplasty, hemiarthroplasty, or maintaining chronic dislocation.8,9 Garver et al.8 highlighted that while some options may alleviate pain, they often result in compromised function post-revision. A cerclage technique was first reported in a single case of persistent instability after revision RSA by securing the humeral prosthesis to the scapular spine with braided nonabsorbable tape.2 Tashjian et al.5 reported three cases of recurrent RSA instability treated with a glenohumeral cerclage consisting of sutures passed through a single drill hole medial to the baseplate and superior to the central post and either tied around the humeral neck or passed through 2 drill holes made in the humerus. An acromiohumeral cerclage was recently described utilizing Kevlar core tapes around the humeral component tied superiorly over an acromial bone bridge.10 Although the authors note no complications in the paper, high-tensile suture used in the transosseous drill holes in acromioclavicular reconstruction has been linked to clavicular and coracoid fractures and similar risks of acromial fractures, have been associated with the size and orientation of bone tunnels.11 As described in this technique paper, The all-suture anchor positioned above the glenoid baseplate offers a comparable cerclage fixation with bone and enhances stability once other options for stabilizing the shoulder have been explored and addressed. From a mechanical standpoint, using the posterior suture limb through the trans-osseous tunnel and an anterior suture limb through the subscapularis creates a double-loop restraint that protects against superior migration and anterior displacement, respectively. [Table 1]

There are several limitations and potential complications associated with this surgical technique. As with any suture anchor, placement of the implant in poorer-quality bone can significantly increase the likelihood of anchor displacement. Additionally, improper positioning of the suture anchor with enough space above the glenosphere may lead to suture impingement on the implant, which in turn can diminish the range of motion, accelerate suture wear, and potentially result in the failure of the glenoid-anchor cerclage. Poor bone bridge for the posterior hole in the humerus can undermine the integrity of the glenoid-anchor cerclage while increasing the risk of fracturing through the tuberosity. Moreover, not addressing other critical factors for instability, such as glenoid lateralization, appropriate glenoid size, correct baseplate positioning, adequate humeral bone stock and length, and proper valgus inclination on the humeral stem, can all contribute to suboptimal results.3 Failure to repair the subscapularis or incorrectly securing the anterior suture can also significantly heighten the risk of anterior instability, undermining the success of the procedure. In summary, potential complications of the glenoid-anchor cerclage technique include anchor displacement, reduced range of motion and construct failure due to suture impingement, and increased risk of tuberosity fracture secondary to tuberosity drilling. Furthermore, it cannot be overstated that other critical factors associated with instability following RSA need to be considered and addressed to ensure the best possible outcome, as these factors can result in excessive stress on the cerclage, which may ultimately lead to its failure and recurrent instability.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Andrew Jawa, MD - This author has the following disclosures to report: AAOS: Board or committee member; American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons: Board or committee member; Boston Outpatient Surgical Suites: Other financial or material support; DePuy, A Johnson & Johnson Company: Other financial or material support; DJ Orthopaedics: Paid consultant, Paid presenter or speaker, Research support; Ignite Orthopaedics: IP royalties; Ignite Orthopedics: Stock or stock Options; Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery: Editorial or governing board; Oberd: Publishing royalties, financial or material support

The remaining authors do NOT have any potential conflicts of interest related to the content presented in this manuscript.

DECLARATION OF FUNDING

The authors received NO financial support for the preparation, research, authorship, and publication of this manuscript.

DECLARATION OF ETHICAL APPROVAL

Institutional Review Board approval was not required for the production of this manuscript.

DECLARATION OF INFORMED CONSENT

There is no information (names, initials, hospital identification numbers, or photographs / images) in the submitted manuscript that can be used to identify patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Kiet LE, PA-C, Boston Sports and Shoulder Center Research Foundation, Waltham, MA, New England Baptist Hospital, Boston, MA, ORCID ID: 0000-0002-2824-4547

_and_subscapularis_(yell.png)

_all_suture_anchor_is_placed_superiorly_above_the_baseplate_with_adequate_clearance_of_.png)

_and_subscapularis_(yell.png)

_all_suture_anchor_is_placed_superiorly_above_the_baseplate_with_adequate_clearance_of_.png)