INTRODUCTION

A buckle, or torus, fracture occurs when the cortex of a bone is compressed and undergoes plastic deformation with a resulting outward bulge, as seen on radiographs.1 Buckle fractures are unique to the pediatric patient due to their softer bone enveloped in thick periosteum. The distal radius is the most common location in which buckle fractures occur, with an incident reported that one in 25 children will sustain a distal radius buckle fracture.2 Pediatric long bones are also unique in that a physis, or growth plate, is present.3 Fractures that impact the physis are graded in severity by the Salter-Harris grades I through V, with Salter-Harris II fractures being the most common. By definition, Salter-Harris II fractures extend from the growth plate into the metaphysis.3 Treatment of Salter-Harris II fractures varies based on the degree of displacement and fracture stability.4

A known complication in adult distal radius fractures is extensor pollicis longus (EPL) tendon rupture with resulting loss of thumb interphalangeal joint extension and retropulsion.5 EPL tendon rupture is most commonly treated surgically with a tendon transfer of the extensor indicis proprius (EIP). Multiple theories have been proposed to explain the attritional wear of the EPL tendon following a distal radius fracture, including a diminished blood supply due to thickening of the tendon sheath, swelling within the extensor compartment, or friction between the tendon and healing bone.6 After surgical fracture repair, contact between the EPL tendon and protruding screws can also lead to mechanical damage and eventual rupture. In a previous case series, Roth et al. reported spontaneous EPL rupture after 5% of non-displaced distal radius fractures in adult patients, occurring an average of 6.6 weeks after the initial injury.7 However, EPL rupture resulting from distal radius fracture has rarely been described in the pediatric population.

CASE REPORT

Patient one: A 14-year-old, right-hand dominant female presented to the emergency department (ED) with pain in her right wrist following a fall while roller-skating. No numbness or weakness was noted on the physical exam, and peripheral perfusion was normal. The patient had full extension and retropulsion of the right thumb. Imaging was obtained in the ED, demonstrating a non-displaced, Salter-Harris II distal radius fracture and avulsion of the right ulnar styloid process. No reduction was required. The patient was treated with a reverse sugar tong splint and discharged. The following day, she presented for an outpatient follow-up. Repeat imaging in the splint was obtained, demonstrating a Salter-Harris II distal radius buckle fracture [Figure 1]. The splint was removed and replaced with a short arm cast.

X-rays were obtained three and six weeks after the initial injury to monitor the healing of the fracture. She was discharged from treatment and regained full wrist function, reporting no lingering symptoms. Ten weeks after her intimal injury, she returned, reporting a sudden inability to extend her right thumb fully; no additional trauma or inciting event was reported. On physical exam she could not perform retropulsion or extend her thumb at both the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and interphalangeal (IP) joints. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was obtained demonstrating EPL tendon rupture [Figure 2 A-E]. The patient was also noted to have an EIP tendon on MRI. The patient was fitted with a thumb Spica brace and scheduled for surgery.

The patient underwent EIP to EPL tendon transfer under general anesthesia. A two-incision approach was performed; the first followed the course of the EPL tendon over the metacarpals, and the second was a small transverse incision proximal to the MCP joint of the right index finger. On inspection of the distal margin of the ruptured EPL tendon, slight fraying was noted at the lacerated end, and there was no evidence of more distal extending degeneration. The EIP tendon was isolated, released, and advanced into the operative field. EIP to EPL tendon transfer was secured with Pulvertaft weaves. Four passes were performed in a perpendicular fashion and secured with 3-0 FiberWire sutures while the thumb was held in extension and retropulsion. The wrist was brought through a range of motion, and tenodesis of the thumb was confirmed. After surgery, a thumb Spica brace was applied, keeping the thumb in extension, adduction, and retropulsion. At her two-week post-operative appointment, she was transitioned into a removable fabrication forearm bases thumb spica orthosis. She began occupational therapy at a frequency of twice a week for eight weeks.

The patient presented for a final follow-up four months post-op and reported full thumb function after being discharged from occupational therapy with no further complaints. On physical exam, the right thumb showed 5/5 strength with retropulsion and extension against resistance at the MCP and IP joints. The patient could oppose the right thumb to the base of the fifth finger and make a full fist with the right hand. The right index finger showed full extension at the MCP joint.

Patient two: A 15-year-old, right-hand dominant male presented to an outside emergency clinic with right wrist pain and obvious deformity immediately after falling off his electric bicycle. X-rays were obtained, and a reverse Colles fracture was diagnosed. While at the clinic, the patient developed an altered sensation over the median nerve distribution of his right hand, and he was sent to our hospital for a closed reduction procedure under general anesthesia. X-rays were obtained during the reduction to ensure proper alignment, and a Salter-Harris II right distal radius fracture and Salter-Harris I ulnar fracture were diagnosed. A plaster and fiberglass short arm cast was applied.

Five days later, at the patient’s first post-op follow-up, the patient reported well-controlled pain and was tapering off pain medications. Sensation was intact to light touch, and capillary refill was brisk on the right hand. X-rays showed a Salter-Harris II distal radius fracture with alignment intact. However, at follow-up two weeks after closed reduction, X-rays showed volar migration of the articular component of the radius and loss of reduction [Figure 3].

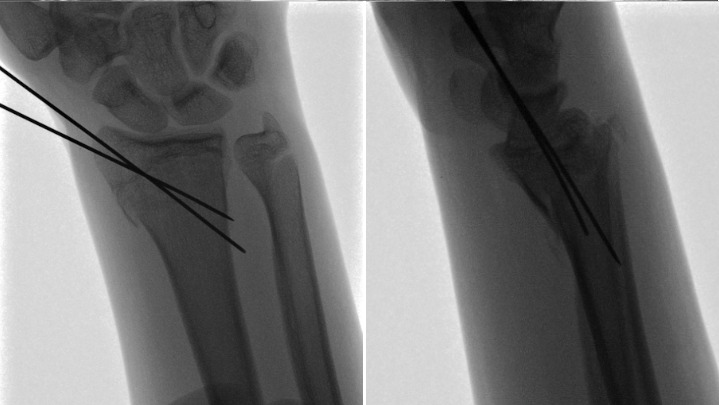

He subsequently underwent repeat closed reduction and percutaneous pinning. [Figure 4] Percutaneous pins were removed at three weeks, and the patient was fitted with a cock-up wrist splint to wear at school and was advised to remain out of sports. At the final follow-up one month later, the patient denied any pain and showed a full range of motion of the right wrist compared to the contralateral side. X-rays confirmed the healing of the fractures, and the patient was cleared for normal activity.

Eight months after being cleared for full activity, he reported feeling a sharp pain in his right dorsal wrist and into his thumb when he was recently wrestling with his sisters, and he has been unable to extend his thumb ever since. The patient returned to our clinic after being seen by another orthopedic group and having been referred for an MRI. On physical exam, the patient could not retropulse or extend the right thumb at the IP joint and displayed tenderness about Lister’s tubercle. The MRI was consistent with an EPL tendon rupture. The following week, an EIP to EPL transfer was performed.

DISCUSSION

Buckle fractures are characterized by bulging of the soft cortex of long bones in children, most commonly in the distal radius, and they are generally very stable and heal with conservative treatment.1,2 Spontaneous rupture of the EPL tendon is a known complication following both displaced and nondisplaced distal radius fractures in adults. Still, it is rare in the pediatric population and has not been well described in association with buckle fractures.5 Masquijo et al. reported an EPL rupture in a 15-year-old female eight weeks after a minimally displaced, extra-articular distal radius fracture that was treated with casting for four weeks.5 Song et al. reported EPL rupture in a 15-year-old male who suffered a nondisplaced Salter-Harris II fracture of the distal radius; the fracture healed with casting for five weeks, but the patient suffered EPL rupture nine weeks after injury.8 These cases demonstrated patients of the same age and similar treatment course and timeline of injury to the first patient in this report, but those fractures were not defined as buckle fractures. Patel et al. reported a Salter-Harris II fracture in a 16-year-old male treated with closed reduction and pinning, who developed an EPL rupture six weeks after injury.9 This case required surgical intervention, similar to the second case in this report, but exhibited a much shorter time between the initial injury and tendon rupture. All reported patients presented with a sudden inability to extend the thumb fully and underwent surgical EIP to EPL tendon transfer, regaining full range of motion and function of the affected thumb.

EPL tendon rupture can be diagnosed through a physical exam and confirmed with MRI. Patients will exhibit limited thumb extension at the IP joint and possible deficiencies at the MCP joint. Additional findings of loss of thumb retropulsion and a possible visible deformity where the EPL tendon runs along the dorsal aspect of the wrist may be encountered.5 A ruptured EPL tendon is best seen on axial wrist MRI, where it is noted to be absent at the level of Lister’s Tubercle and appears irregular and fragmented just ulnar to the tubercle.10 However, the EPL tendon can be difficult to track on MRI, and the angle made between the plane of imaging and the orientation of the tendon can alter the signal intensity; a “magic angle” of 55 degrees has been identified at which signal intensity is highest and can be mistaken for tendon pathology.11 EPL tendon rupture post distal radial fracture is most commonly treated with EIP tendon transfer because rupture often occurs secondary to tendon attrition with resulting frayed ends, making primary repair less feasible. Primary tendon repair is applicable in acute rupture of the EPL tendon due to direct trauma, as seen following a laceration.12 96.5% of patients have an EIP tendon. In those that do not have an EIP tendon, tendon grafting, usually involving the palmaris longus tendon, can be used to repair the EPL.12 This procedure is often not preferred, given its increased difficulty and risks.

Multiple theories explain why the EPL tendon ruptures after radial fractures. The EPL tendon takes a unique course and wraps around Lister’s Tubercle, using it as a pulley for the obliquely oriented terminal portion of the tendon. In displaced radius fractures, increased friction between the tendon and bone fragments or surgical hardware in this area may cause the tendon to rupture. When a non-displaced fracture is present, it is theorized that ischemia may contribute to EPL rupture. Just proximal to Lister’s Tubercle, the EPL musculotendinous junction is poorly vascularized due to a watershed in the two main vascular systems from proximal and distal regions.13 Increased pressure in the tendon sheath, secondary to effusion or hematoma from the distal radius fracture, can interrupt the already minimal blood flow to the tendon. Similarly, EPL runs within the extensor retinaculum, and it has been theorized that forming a bony callus during fracture healing compresses the tendon within this enclosed space, causing damage.5 In the first case detailed in this report, buckling of the distal radius may have compressed the EPL tendon against the extensor retinaculum, reducing blood flow and increasing friction. While tendon rupture occurred after the fracture fully healed, the combination of damage during the healing process, irritation from callus formation, and increased use of the hand and wrist after the cast was removed could have resulted in the rupture. The second case in this report was unique in that EPL tendon rupture occurred much later after the initial injury than any other reported case; this long delay also makes it unlikely that the closed reductions or pinning procedures caused damage to the tendon that directly led to the rupture. It is possible that repeated displacement of the fracture, in this case, caused minor damage to the EPL tendon that could not fully heal due to poor vascularization in the area. This predisposed the patient to tendon rupture when participating in a vigorous activity like wrestling.

While spontaneous EPL tendon rupture following recovery from a distal radius fracture is uncommon in the general population, it is even less common in pediatric patients; however, providers should still inform patients of the warning signs for this complication. Patients should be aware that dorsal wrist pain persisting after pain from the initial fracture has subsided, potentially exacerbated by repetitive thumb extension, which may be a sign of EPL tenosynovitis that could lead to rupture.12 Extra care should be taken in surgical repairs of distal radius fractures to avoid placing any hardware or leaving bone fragments in the direct path of the EPL tendon. Additionally, patients should be counseled to limit swelling, which may compromise blood flow, through medication and elevation of the injured arm. While buckle fractures are generally uncomplicated and treated conservatively, providers should maintain a level of suspicion of EPL tendon injury due to its susceptible nature.

While rare, EPL tendon rupture can occur in the pediatric patient after a seemingly uncomplicated buckle fracture or fracture that was healed for an extended period after closed reduction and pinning. Awareness of this complication is required to provide prompt intervention.

Declaration of conflict of interest

The authors do NOT have any potential conflicts of interest for this manuscript.

Declaration of funding

The authors received NO financial support in the preparation, research, authorship and publication of this manuscript.

Declaration of ethical approval for study

The IRB at this institution does not require approval for case reports.

Declaration of informed consent

There is no identifiable information in this manuscript