Introduction

Xylazine-related wounds are increasingly presenting a surgical dilemma in people who use drugs (PWUD).1 Initially developed as a veterinary sedative, xylazine has been found increasingly added to illicitly manufactured fentanyl, reportedly to extend the duration of fentanyl intoxication.2 On the street, xylazine-laced fentanyl is known as “tranq,” “tranq dope,” “zombie drug,” and “Philly dope”.3 Xylazine use among PWUD has led to a surge in complex soft tissue wounds, characterized by progressive necrosis and delayed wound healing that can begin superficially but progress to deeper tissue invasion, potentially compromising limb viability. The underlying pathophysiology is likely multifaceted, including tissue hypoxia resulting from local vasoconstriction, as well as direct tissue chemical toxicity. But unlike other injection drug-related wounds, xylazine-associated wounds exhibit a unique pathophysiology, sometimes developing at sites distant from the injection area, suggesting a systemic component. Furthermore, patients requiring surgical management of xylazine-associated wounds need multidisciplinary care, initially to manage withdrawal symptoms and initiate medication for substance use disorder (SUD), as well as ongoing support to facilitate wound healing and promote SUD recovery. The complex interplay between SUD, varying severity of xylazine-associated wounds’ surgical management, and the need for prolonged care beyond the initial hospital course to maintain adherence and optimize outcomes is a challenging clinical problem for the multi-disciplinary team needed for successful patient care. Moreover, because this is a relatively new phenomenon, concentrated mainly in the Philadelphia area, there is limited evidence to guide treatment.

Consensus Meeting Purposes

On November 23, 2024, the symposium The Next Chapter of the Opioid Epidemic in Pennsylvania: “The Xylazine Crisis” was held at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College in Philadelphia, PA, USA and hosted by the Rothman Institute Foundation for Opioid Research & Education. This event brought together leading experts in orthopaedic surgery, plastic surgery, burn surgery, addiction medicine, internal medicine, family medicine, emergency medicine, toxicology, public health, and policy to address the growing concerns surrounding xylazine, a potent non-opioid veterinary sedative increasingly linked to opioid-related complications across the Philadelphia metropolitan region.

Discussions highlighted the clinical challenges posed by xylazine, with representatives from the Rothman Orthopaedic Institute, Drexel University College of Medicine, Cooper University Hospital, Temple University Hospital, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Public Health professionals, and local legislators from the Pennsylvania General Assembly providing insights into its effects on patients, medical and surgical challenges, and public health dynamics.4 Policymakers and city officials also explored legislative and harm reduction strategies to curb its spread, emphasizing the need for coordinated interventions. In addition, surgeons and addiction specialists reviewed approaches to managing xylazine-related toxicity, treating complex wounds, managing addiction and withdrawal, integrating harm reduction into medical and surgical care, and promoting access to ongoing evidence-based SUD treatment.

The purpose of the symposium was to facilitate collaboration between healthcare providers and policymakers, increase awareness, inform policy discussions, and promote best practices to address the evolving xylazine crisis in Philadelphia and beyond.

Objectives

The objective of this consensus paper is to provide a consensus recommendation for managing xylazine-associated wounds embracing a coordinated surgical and medical strategy as well as public health policy considerations.

The recommendations here emphasize the need for a multidisciplinary approach to addressing a complex problem that spans medical, surgical, social, and public health arenas. The recommendations offered are derived from current clinical evidence and expert opinion.

Xylazine Overview

Xylazine is primarily used in veterinary medicine for sedation, analgesia, and muscle relaxation. It acts by binding to alpha-2 adrenergic receptors in the central nervous system, reducing norepinephrine release and producing sedative, analgesic, and sympatholytic effects.5 Xylazine is not approved for human use. Human exposure is most often due to its presence as an adulterant in illicitly manufactured fentanyl. The pharmacological effects of xylazine include potent vasoconstriction, which diminishes blood flow to tissues and leads to ischemia, a key factor potentially contributing to necrosis and other forms of tissue damage. Prolonged ischemia, especially at injection sites, exacerbates the risk of ulceration and progressive tissue necrosis.5 It is also postulated that there is a local tissue toxicity associated with xylazine from its pH-lowering effect.5 Additionally, xylazine’s sedative properties may obscure the patient’s awareness of tissue injury, delaying intervention and complicating wound management.6

Consensus: Xylazine, a veterinary sedative, is being mixed with illicitly manufactured fentanyl. This practice is associated with severe wounds in people who use drugs, likely due to repetitive injections and a complex, multi-faceted disease process.

Epidemiology of Xylazine-Associated Wounds

There has been increasing detection of xylazine in illicit drug samples. Cities such as Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Camden have reported a growing number of individuals using fentanyl who also test positive for xylazine.7 This trend has been accompanied by an increase in severe soft tissue injuries, often presenting as complex wounds involving necrosis, infection, and extensive tissue loss. PWUD presenting with xylazine-associated wounds frequently have severe SUD, complicating both addiction medicine treatment and surgical management of their wounds, necessitating a multidisciplinary approach to clinical management. Furthermore, PWUDs are among the most marginalized groups facing enormous health challenges from an individual (homelessness, poverty, malnutrition, lack of social support, disrupted family relationships), institutional (difficulties with access to care, judgmental staff attitudes), community (stigma and blame), and financial and policy (the failed war on drugs) perspective.

Consensus: Xylazine-associated wounds are increasing in prevalence in urban sites with a high concentration of PWUD. This highly marginalized population has complicated medical and surgical needs. Lack of attention to social drivers and limited access to comprehensive SUD treatment and consistent surgical strategies have led to delays in seeking care and increased complications.

Clinical Presentation

Xylazine-associated wounds typically present in progressive stages, beginning with erythema, swelling, and tenderness at the injection site, often accompanied by superficial ulceration or necrosis. As the wound advances, the ischemic effects of xylazine contribute to deeper tissue loss, with ulcerations and necrosis becoming more pronounced. In progressive cases, necrosis extends to the muscle and fascia, and in severe instances, bone exposure, osteomyelitis, and necrosis can occur. Commonly, patients with advanced tissue necrosis present with chronic malodorous wounds, often with exposed tendons and bone.8 Chronic non-healing wounds, despite prior medical interventions, are frequently observed in these patients, exacerbated by environmental factors, such as lack of access to soap and water, social factors such as homelessness, and continued local substance use and secondary infections such as osteomyelitis are frequent sequelae. Interestingly, significant wound healing has been observed in patients with periods of sobriety. Classifying these wounds and guiding treatment can be a challenging task. Imaging can also be misleading, given the periosteal inflammation and air in soft tissue, which can reflect recent injection sites versus necrotizing fasciitis. The overall clinical assessment should determine whether the infection is local or systemic but may be complicated by the presence of dramatic wounds in the setting of bacteremia, endocarditis, renal failure, and other systemic infections. In advanced cases, limb viability may be compromised due to exposed bone, tendon destruction, nerve damage, and limb ischemia. The progressive nature of these wounds requires close monitoring and early therapeutic measures to mitigate limb compromise.9

Consensus: Xylazine-associated wounds are complex wounds that can have varied presentations, warranting a broad range of surgical, medical, and wound care management needs.

Classification of Xylazine-Associated Wounds

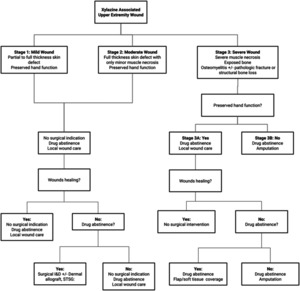

Xylazine-associated wounds can be classified based on tissue destruction severity to guide treatment decisions and potentially predict outcomes.10,11 Tosti et al. have previously presented a xylazine-associated wound treatment algorithm formulated by senior author Criner-Woozley KT and adopted by the members of this consensus paper,10,11 which is coined “The Philadelphia Treatment Algorithm for Xylazine Wounds” [Figure 1].

Stage 1, mild wounds, involve skin violation only, partial or full thickness, but with no muscle involvement and preserved extremity function [Figure 2].

Stage 2, moderate wounds, involve deeper violation with full-thickness skin compromise, minor muscle necrosis, and preserved extremity function [Figure 3].

Stage 3, severe wounds, involve extensive soft tissue violation, with muscle and tendon necrosis, exposure of bone, osteomyelitis, and sometimes pathologic fracture due to osteomyelitis. Stage 3 severe wounds are further classified based on the preservation of hand function distally per Tosti et al.10 This sub-classification can be extrapolated to the foot for lower extremity xylazine-associated wounds. Stage 3A has preserved hand function [Figure 4].

Stage 3B involves wounds without hand function [Figure 5].

Consensus: Xylazine-associated wounds should be characterized through the straightforward “Philadelphia Algorithm” to guide the surgical strategy of Xylazine-associated wounds.

Management Paradigm

Effective management of xylazine-associated wounds calls for a genuine multidisciplinary team approach to address both the wound pathology and the underlying substance use disorder.1,10 Members of this team should include addiction medicine, infectious disease, wound care, social work services, peer support, and the surgical team. Surgical specialists may consist of general surgery, plastic surgery, burn surgery, orthopaedic surgery, and hand surgery.

Consensus: A multidisciplinary approach should be deployed to treat both the xylazine-associated wound and the patient’s underlying substance use disorder. A lack of interdisciplinary coordination will diminish the likelihood of success in both surgical and addiction treatment.

Medical Management

Barring imminent life or limb compromise from xylazine-associated wounds, medical management, including addiction medicine, infectious disease, hospital medicine, and primary care, as appropriate with ongoing local wound care and social service support, should be undertaken before active surgical reconstruction. The significant and complex health-related social needs of individuals with xylazine-related wounds often lead them to emergency departments and acute care hospitals as a default. To address this, acute care settings must develop robust warm hand-off protocols to connect these patients with settings that are better equipped to meet their ongoing, complex needs and facilitate long-term recovery. Hospital social work staff need support in building partnerships with post-acute care facilities (including acute/sub-acute physical rehabilitation and skilled nursing facilities) that are knowledgeable about the specific needs of individuals in early recovery from opioid use disorder (OUD).

Consensus: Xylazine-associated wounds result from both tissue ischemia and local chemical toxicity; therefore, the first step in management is the initiation of medical management, evidenced-based SUD treatment, and establishment of social service support before extensive surgical intervention is deployed.

Addiction Medicine

Addiction medicine plays a crucial role in engaging the patient with opioid use disorder and addressing the underlying disease process. Evidence-based care can prevent and treat opioid withdrawal, address pain appropriately, decrease cravings and continued use, and help limit self-directed discharge. An acute care hospitalization for serious injection-related infections and complex wounds offers a unique opportunity to initiate medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) treatment with methadone or buprenorphine in a controlled setting. Recommendations for MOUD initiation can be made by addiction medicine consult services and expedited through the use of withdrawal and MOUD initiation order sets developed by addiction medicine specialists. They should reflect dosing needs based on the local drug landscape. Optimizing pain management by combining appropriately dosed full opioid agonists with multimodal pharmacological treatment and adjunctive interventions such as nerve blocks is critical. This pain management should take into account an individual patient’s use patterns, including amounts, routes, and chronicity. Training hospital social services staff in the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) level of care assessment may contribute to optimal placement, continued service, and transfer of patients seeking ongoing addiction treatment services once acute medical conditions have stabilized. Dedicated social work, case management, and peer navigator staff can provide life-saving linkages to ongoing outpatient care in the community. Trained peer navigators are essential team members, providing a trusted source of early recovery support services and tailored care and coordination. Unplanned or patient-directed discharges, while suboptimal, should be anticipated with explicit contingency planning for ongoing treatment and linkage to care documented in the chart by addiction medicine and other specialists as indicated. Increasing numbers of safety-net primary care settings are offering ongoing MOUD treatment and are often a critical low-barrier option to reconnect patients with care who have left the hospital prior to completing treatment.

Infectious Disease

Xylazine-related wounds are exposed soft tissue wounds that are inherently contaminated with poly-microbial flora. Infections can vary from superficial infection to bacteremia and osteomyelitis. As such, antibiotic treatment in consultation with infectious disease consultants can aid in guiding the type and duration of treatment. However, these wounds, although colonized, are often not infected, and unnecessary antibiotic use should be avoided to prevent resistance and other complications.

Wound Care

Wound care specialists facilitate local wound care centered around secondary intention wound healing. The basis of wound care is regular wound cleaning, keeping the wound moist, and covering it with a non-constrictive and non-adherent dressing. Xylazine-associated wound care should be performed daily, starting with cleaning the wound with warm water or saline and a mild soap or foam wound cleanser. Various strategies include moist wound care with autolytic debridement, bedside mechanical debridement, wet-to-dry changes, chemical debridement, and negative pressure therapy with vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) application and maintenance. Regular wound care, even in the setting of continued Xylazine use, has shown impressive wound-healing outcomes. Enzymatic debridement to the entire wound, such as Silvadene (Silver sulfadiazine 1%), should be considered for more contaminated wounds. Moist petroleum-based ointments can be applied to the cleaner wound beds (Aquaphor or A+D ointment). A non-adherent dressing, such as Xeroform, should be used for drier wound beds, and Adaptic for moist wound beds. An army battle dressing (ABD) dressing can be applied, followed by a light, non-compressive wrap to keep the dressing in place (such as Kerlix gauze wrap and/or an Ace bandage dressing loosely.

Social Services

People who use drugs presenting with advanced xylazine-associated wounds frequently experience significant socioeconomic challenges, including malnutrition, unstable housing, limited social support, and health insurance disparities. Given this complexity, robust social work involvement is essential to coordinate comprehensive care and ensure access to vital resources such as street and mobile wound care. Moreover, the unique barriers faced by PWUD often restrict access to nursing facilities and detox facilities, underscoring the critical need for adequate social service support to facilitate adherence to surgical and medical treatment plans.

Surgical Management

Although early surgical consultation for a patient presenting with a xylazine-associated wound to stage the wound and possible preoperative planning is warranted, early surgical intervention is discouraged, barring imminent life or limb compromise from the xylazine-associated wounds.

Consensus: Xylazine-associated wounds result from tissue ischemia and local chemical toxicity; therefore, with abstinence from continued use of xylazine, surgical needs may evolve over time. In contrast, without abstinence, most surgical interventions will fail and have surgical complications. Once active engagement and adherence with addiction medicine treatment have been confirmed, surgical reconstruction warrants can be undertaken on a staged basis with regular reassessment to optimize the potential for surgical success and to more responsibly deploy surgical resources.

Depending on the hospital and its resources and expertise, surgical consultants could potentially include general surgery, plastic surgery, burn surgery, orthopaedic surgery, and hand surgery. Often, a collaborative approach is necessary as surgical expertise may require various surgical specialty lines, including debridements, grafts, flaps, and bone reconstructions.

Stage 1

For Stage 1 wounds, management typically involves nonoperative measures. Treatment should begin with good daily hygiene, including washing with soap and water. Bedside wound debridement should focus on autolytic debridement with moist wound care, petroleum, bacitracin, hydrogel, and Silvadene. Wet-to-dry dressing changes are used to remove necrotic tissue but are often poorly tolerated. Chemical debridement with topic agents such as Santyl® and topical antibiotics can also aid in wound debridement and encourage new tissue granulation. Negative pressure therapy with a VAC can also be utilized for fully debrided wounds and fill in soft tissue loss to prepare for split-thickness grafting. Antibiotic therapy is dictated by the presence and extent of active infection versus the presence of a stable but colonized wound bed.

Consensus: Stage 1 Xylazine-associated wounds are generally superficial and best managed non-operatively with wound care strategies.

Stage 2

For Stage 2, surgical intervention is generally required due to the wound depth and deep structure violation. Initial surgical interventions focus on gentle debridement to remove necrotic tissue while maintaining surrounding soft tissue. Aggressive debridement may increase the rates of exposed bone and tendon. Once the wound has stabilized, reconstructive strategies can be applied, including synthetic dermal substitutes to maintain and support soft tissue in patients not in maintained cessation. Skin grafting or flap reconstruction in the setting of exposed and/or infected bone should be reserved for patients in maintained cessation of xylazine use. Temporizing the wound bed with a synthetic dermal substitute can support surrounding soft tissue over exposed bone and tendon. It can prevent or delay the progression to amputation while patients engage in recovery services. Patients who have successfully engaged in prolonged cessation can heal to completion without the need for skin grafting. When considering free flaps, assessment of the local vasculature’s integrity is necessary, as it may have been compromised by the local wound, infection, or xylazine-related toxicity. When bone is exposed, osteomyelitis can be assumed to be present, and bone debridement and antibiotic treatment should be deployed as indicated, while hardware should be avoided.

Consensus: Stage 2 Xylazine-associated wounds generally require a coverage strategy but are best managed early with limited debridement and time to allow for wound convalescence with xylazine abstinence prior to pursuing wound coverage or reconstruction.

Stage 3

For Stage 3, surgery is predicated by the preservation of distal appendage function – the hand or feet for the upper and lower extremities, respectively. Stage 3A assumes maintenance of hand or foot function, and surgical reconstruction should be centered on its preservation. This is often complex and requires addressing multiple tissue types, including bone, soft tissue, and tendon. A stable skeleton and adequate soft tissue must be achieved before an attempt can be made to provide motor function to the extremity. Distal sensation patterns must be understood and maintained relatively intact to consider reconstruction. Patients must understand that “normal” extremity function will no longer be possible. Instead, the goal is to preserve specific functions of the extremity, allowing these patients to perform activities of daily living and work-related tasks. We believe that a sensate limb with partial function is often a better option than amputation/prosthesis. The goals of reconstruction may vary for each patient, with compliance being crucial for achieving a satisfactory result. Vascularized or non-vascularized bone grafting may be required to achieve a stable skeleton. Soft tissue reconstruction is often in the form of free tissue transfer, which can be challenging due to the limitations of arterial and venous insufficiency of the injured limbs. Tendon reconstruction can only be performed if adequate soft tissue is present. This is often in the form of tendon transfer or intercalary tendon grafting. At this point, patient compliance is critical for a successful outcome.

In contrast, Stage 3B assumes compromised hand or foot function, and therefore, primary amputation may be considered. This is discussed on a case-by-case basis, often involving family members and non-surgical consultants. We do believe that amputation is a form of reconstructive surgery. We recommended pre-operative consultation with prosthetists so that patients can understand their options and determination can be made about the appropriate level of amputation. Regenerative peripheral nerve interface surgery and targeted muscle innervation can be used to manage neuroma pain at the time of the index amputation or as a secondary treatment. It is important to choose a level of amputation that will allow for stable soft tissue closure to minimize post-operative complications. We have seen that removing the significant wound burden from these patients in a non-functioning extremity removes significant stigma and allows patients to re-enter society. However, if amputation is determined to be the best choice, it is essential to confirm that adequate informed consent has been obtained, the patient’s competency is not in question, and more than one surgical consultant has documented in the chart the need for an amputation.

Consensus: When a xylazine-associated wound has resulted in severe limb compromise, whether to salvage or amputate should be based on the potential distal appendage (hand or foot) functionality. Anytime an amputation is being considered, there should be an assessment and clear documentation of the patient’s ability to consent to treatment by the appropriate non-surgical consultant, such as a psychiatrist, as well as two or more surgical consultants agreeing that amputation is the best surgical option for the patient.

Ethical Considerations

Surgical interventions to treat xylazine-associated wounds often require extensive medical resources, long-term antibiotic therapy, and physical rehabilitation. This is in contrast to the management of these wounds without surgical intervention, which may be achieved through routine wound care while addressing the underlying addiction using both harm reduction and evidence-based medications for opioid use disorders. Care should be provided equitably to ensure that all patients, regardless of their substance use history, have access to the necessary care to address both the wound and the underlying addiction.

Informed consent in patients with SUD may be complicated by impaired decision-making capacity, requiring healthcare providers to assess the patient’s ability to provide informed consent before proceeding with treatment. The principle of beneficence can guide decision-making for patients with impaired decision-making capacity in the emergency setting. However, the principle of autonomy may supersede once the patient is stabilized. The question of the impact of SUD on decision-making capacity and its threat to autonomy challenges physicians to determine how much weight to give to this principle in various scenarios.12

The ability to assess autonomy in the setting of SUD is confounded by a patient’s ability to understand and appreciate the risks associated with their decision. There are questions as to whether patients faced with decision-making upon presentation to the hospital could be suffering from acute toxicity, acute withdrawal symptoms, or even the chronic effects of opioid use on the brain that impair cognitive function.13 This question is complicated by the fact that naloxone administration in the setting of xylazine co-administration with fentanyl worsens withdrawal and is associated with distinct withdrawal symptoms not seen with fentanyl alone, questioning the need for a distinct set of pharmacologic interventions in this scenario.14,15 Opioid use alone has been shown to upset the equilibrium between a person’s reflective versus reflexive decision-making, with the impact of xylazine unclear.12 This can be despite the ability of these patients to clearly restate back detailed concerns voiced by healthcare professionals, implying competence and understanding while still demonstrating higher risk-taking and delay discounting, making a choice that tends to favor immediate rewards over long-term benefits to health, the effects of which can impact decision making for even 18 months after cessation of opioid use.16

SUD has been shown to compel users to pursue riskier choices, often even rejecting mild intervention recommendations such as simple observation.17 Ultimately, the most impactful long-term benefit to xylazine-associated wounds is addressing the underlying substance use disorder and wound care management. Although surgical intervention will provide faster clinical outcomes, these results are not sustained without addressing the underlying addiction driving the behaviors that trigger the development of these wounds in the first place.

Consensus: Given the high risk of recurrence without addressing the substance use disorder, the option for surgical intervention is best considered in the setting of addiction management and not in the acute care of these patients. This approach balances the principles of beneficence while addressing the challenges of identifying true autonomy in decision-making in the setting of OUD.

Conclusion

On November 23, 2024, the symposium titled “The Next Chapter of the Opioid Epidemic in Pennsylvania: The Xylazine Crisis” was held, bringing multi-disciplinary physicians and surgeons across the major medical centers in Philadelphia, actively managing xylazine-associated wounds among people who use drugs. Xylazine, a veterinary sedative, is being mixed with illicitly manufactured fentanyl. This practice is associated with severe wounds in people who use drugs. A consensus was formulated to better guide treatment while providing treatment evidence for other urban areas also beginning to manage xylazine-associated wounds. The consensus included the need for a multidisciplinary approach crossing medical, surgical, social, and public health expertise. The recommendations offered are derived from current clinical evidence and expert opinion. A lack of multidisciplinary coordination will diminish the likelihood of both surgical and addiction treatment success.

Declaration of conflict of interest

The authors do NOT have any potential conflicts of interest for this manuscript.

Declaration of funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript. The consensus was hosted and paid for by the Rothman Institute Foundation for Opioid Research & Education.

Declaration of ethical approval for study

N/A

Declaration of informed consent

There is no information (names, initials, hospital identification numbers, or photographs) in the submitted manuscript that can be used to identify patients.

_from_the_same_patient.png)

.png)

__but_with_intact_hand_function.png)

__but_without_preserved_hand_function.png)

_from_the_same_patient.png)

.png)

__but_with_intact_hand_function.png)

__but_without_preserved_hand_function.png)