Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a procedure with a 150-year history, with the posterior approach (PA) first described in 1874 and performed in 1891.1,2 THA has undergone many advancements, including the implementation of minimally invasive approaches. Currently, there are four main approaches used to perform a THA. The PA was the first approach, followed by the direct anterior approach (DAA), then the anterolateral approach (ALA), and the direct lateral approach (DLA).1 Since their original publication, modifications have been made to these approaches to adapt the techniques to modern medical practice. This evolution has led to the modern THA, which is widely regarded as one of the most successful orthopedic procedures available, with over 450,000 procedures performed in the United States annually.3 Outcomes following the different approaches have been well investigated. However, there is still debate about which approach leads to the best outcomes, and the emphasis on patient satisfaction and reducing healthcare costs has increased interest in this question.4,5 This paper aims to examine recent literature on patient outcomes of total hip arthroplasty (THA) based on the approach.

Our search protocol was as follows

Inclusion criteria were any paper discussing the surgical approach, including narrative reviews and Level 1-5 evidence papers. We excluded articles in languages other than English. The following searches were conducted via PubMed advanced search builder to find and review papers for inclusion or exclusion based on their relevance to the topic of the review of the current concepts. Additionally, references for relevant papers were also used to find manuscripts relevant to the sub-topics of the current concepts review.

1: (((total hip arthroplasty) AND (direct anterior approach)) AND (posterior approach)) AND (primary) – 144 results

2: ((((total hip arthroplasty) AND (direct anterior approach)) AND (direct lateral approach)) AND (anterolateral approach)) AND (primary) – 27 results

3: ((((total hip arthroplasty) AND (direct lateral approach)) AND (anterolateral approach)) AND (posterior approach)) AND (primary) – 17 results

4: ((((total hip arthroplasty) AND (approach)) AND (comparison)) AND (outcomes)) AND (primary) – 155 results

Pathophysiology Indicating a Need for THA

THA is a highly successful procedure that can vastly improve the quality of life of patients.6 The decision to undergo a THA is made through shared decision-making with the patient, focusing on clinical manifestations such as a lack of response to initial conservative therapy, severe pain, or substantial functional limitation.7,8 Radiographical findings are used to characterize the significance of degenerative joint disease, which provides additional evidence to determine if THA is indicated.7,9 Objective scales like the Kellgren-Lawrence system for osteoarthritis utilize the degree of joint space narrowing, osteophytes, bone sclerosis, and bone cysts to measure osteoarthritis (OA) severity [Table 1].10 Furthermore, perceived surgical risk, as determined by standard methods such as the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) criteria, must also be considered when deciding whether THA is appropriate.8,11

Anatomy of the Hip Joint and Surrounding Structures

The approaches of THA differ based on the anatomical structures that need to be navigated during the procedure. The hip joint is a ball-and-socket joint that allows for a wide range of movements. The femoral head rests inside the acetabulum, formed by the three pelvic bones: ischium, ilium, and pubis.12,13 The labrum and the hip joint capsule stabilize the femoral head within the acetabulum. The joint capsule is made of three ligaments: iliofemoral, pubofemoral, and ischiofemoral, all of which act to limit excessive movement and protect against injury.12,13 The hip is also surrounded by muscles organized into four categories: hip flexors, external rotators, hip abductors, and hip adductors. These muscle groups are crucial for gait mechanics, thus necessitating care to minimize damage during the procedure.12,13

THA approaches must manage important neurovascular bundles surrounding the hip since damage to any of these structures may result in severe and permanent sequelae. The structures at risk of injury include the lateral femoral circumflex artery (LFCA), as well as the superior gluteal, lateral femoral circumflex (LFCN), sciatic, and femoral nerves.12,13 Individual risk differs based on the surgical approach and will be discussed in the sections below.

Common THA Surgical Approaches

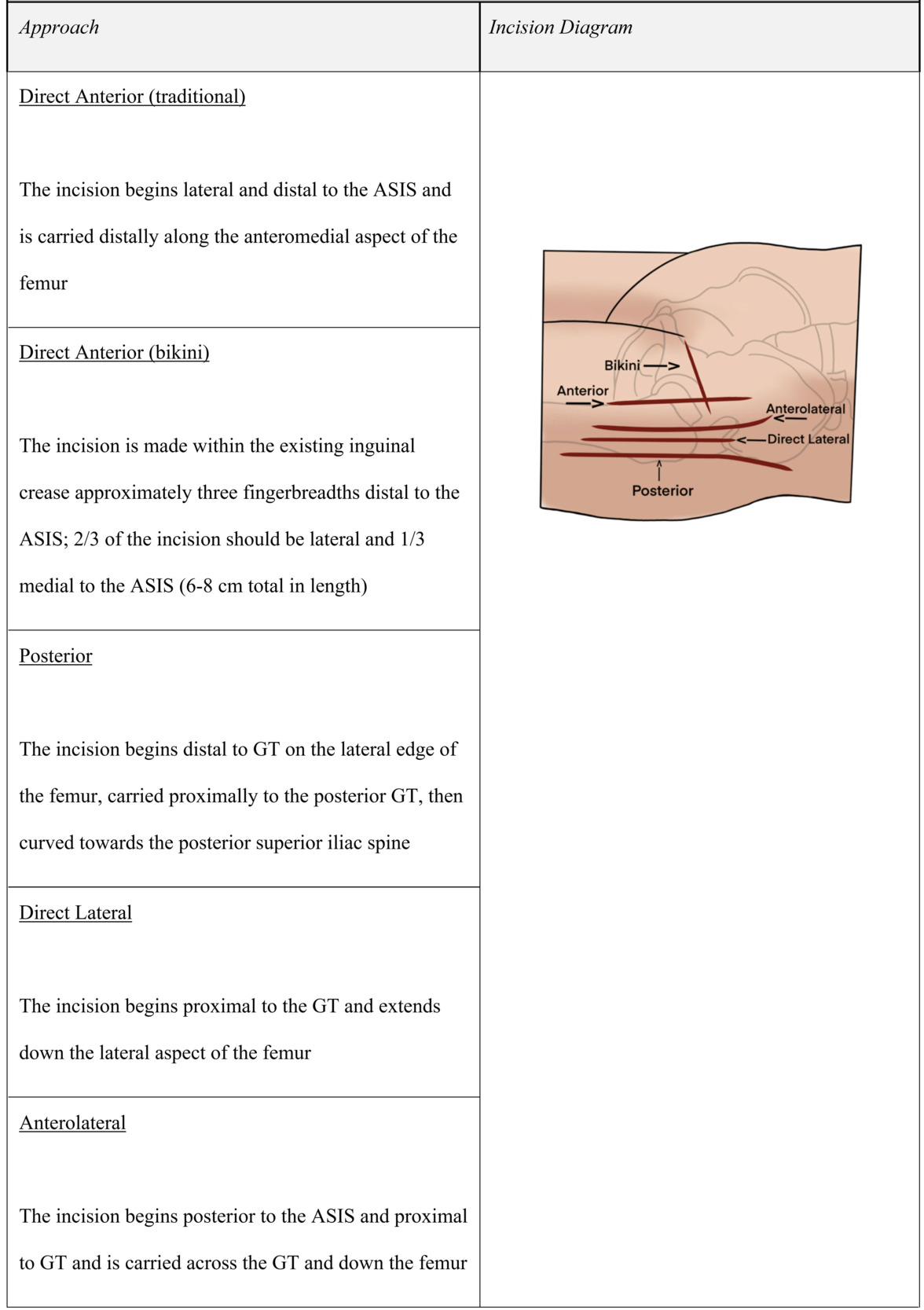

The common surgical approaches are the PA, DLA, DAA, and ALA in order of popularity (ALA and DLA are often grouped as “lateral approaches” or LA).14 Each approach has its own unique incision site, structural navigation, and complications [Table 2].

Direct Anterior Approach Technique

For the DAA, patients are positioned supine – either on a conventional table with an underlying hip bump or on a specialized traction table. The incision is made lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and carried distally towards the lateral aspect of the ipsilateral knee [Table 3]. The fascia overlying the tensor fascia lata (TFL) is excised, and the existing plane between the sartorius and TFL is utilized to access underlying structures.15 The use of this true inter-nervous and intermuscular plane negates the need for muscle detachment or tenotomy, which is theorized to improve outcomes.16,17 The underlying rectus femoris and gluteus medius are retracted to visualize the anterior hip joint capsule, which is excised to access the hip joint.15 During the DAA, important structures to be identified and protected are the LFCN and the ascending branch of the LFCA.

Skeptics of the DAA cite limitations in the extent of femoral exposure, which can make accurate positioning of femoral components more difficult and confer an added risk of intraoperative femoral shaft complications.18,19 Additionally, patients with large abdominal panniculus are at increased risk of incision site complications due to the anteriorly located incision.20 However, the use of a modified bikini incision has been shown to significantly reduce the risk of surgical site complications in patients with a body mass index (BMI) greater than thirty.21

Posterior Approach Technique

The PA is typically performed with the patient in a lateral decubitus position. The PA creates a surgical plane by splitting the muscle fibers of the gluteus maximus.15,18,22 The PA incision begins 3-5 cm distal to the greater trochanter (GT) at the lateral femoral diaphysis. The incision continues proximally along the posterior border of GT and then curves toward the posterior superior iliac spine for 5-8 cm [Table 3]. The fascia lata is visualized and incised over the gluteus maximus, which is bluntly dissected to gain access to the external rotators. The piriformis is identified, and the external rotators are released, allowing access to the posterior joint capsule. Although the PA involves muscle excision, it benefits from sparing the majority of abductor muscles, which reduces the risk of gait disturbance.15,18

The PA allows for excellent visualization of the femur and acetabulum, with a low risk of fracture. However, the sciatic nerve is at risk of injury in the PA due to its course directly inferior to the piriformis and close relation to the posterior hip (average of 1.31 cm between the sciatic nerve and lesser trochanter), so it must be identified and protected.14,15,19

Direct Lateral Approach Technique

The DLA begins with an incision 2-4 cm proximal to the anterior third of the GT that extends in line with the femur 4-6 cm distal to the GT [Table 3]. The underlying TFL and gluteus maximus muscles are identified, and the fascia is split longitudinally at the interval between these muscles. The deeper gluteus medius and vastus lateralis muscles are visualized, and both are bluntly dissected and split to access underlying structures. The gluteus medius is first split at the junction of the anterior-middle thirds. The vastus lateralis is then split just distal to the vastus ridge, extending proximally through the tendinous insertion of the gluteus medius until the muscular split of the medius is reached. Lastly, the gluteus medius, vastus lateralis, gluteus minimus, and anterior hip capsule are released to access the hip joint.15,18,22

The DLA provides good exposure to the acetabulum and proximal femur with the additional benefit of low dislocation rates.15,19 However, there is a risk of disrupting gait mechanics during the release of the gluteus minimus and medius muscles by either failure of abductor layer repair or injuring the superior gluteal nerve (SGN).19 To avoid SGN injury, the incision should not extend proximally past the GT [Table 3].2,22,23

Anterolateral Approach Technique

The ALA attempts to take advantage of the lateral and anterior approaches, exploiting an intramuscular plane between the TFL and gluteus medius muscles while also partially detaching the deep abductor muscles for enhanced acetabulum exposure.22 This approach begins with an incision 2.5 cm posterior and distal to the ASIS and runs towards the GT down the femur [Table 3]. The fascia lata is incised, and the interval between the TFL and gluteus medius is identified and used to access deeper structures. The gluteus medius tendon is partially or fully released to visualize the capsule, which is incised to access the hip joint.

The ALA and DLA are similar, but the ALA attempts to limit injury to the abductor muscles by sparing the gluteus minimus to reduce the incidence of Trendelenburg gait.24 Furthermore, the ALA does not impact any posterior soft tissue, which confers lower rates of dislocations and makes it the preferred approach for THA due to femoral neck fractures.25

Comparison of Outcomes Based on Approach

Patient outcomes following various surgical approaches for total hip arthroplasty (THA) have been a recent topic of interest, with a focus on pain scores, patient-reported outcomes (PROMs), functional recovery, long-term success, and complication rates. The DAA has generated interest due to literature demonstrating possible benefits in early postoperative outcomes.17,26 This paper will review recent literature measuring outcomes based on surgical approaches, specifically comparing the DAA to the three main approaches.

DAA Versus PA

The most recent literature has focused on comparing the DAA and PA due to reports suggesting that the DAA is associated with improved early pain relief, better functional recovery, and the ability to forego postoperative hip precautions.27,28 More recently, studies have compared the DAA and PA in pain, functional recovery, and complication rates.

Pain Outcomes

Recent evidence suggests DAA confers decreased pain earlier in recovery, supported by decreased use of narcotic medication and lower visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores. Three papers measured VAS score and narcotic use in DAA versus PA. Patients in the DAA group experienced significantly decreased pain within two weeks but not beyond.29–31 Of note, one study measured for clinical significance, which found the differences in pain and narcotic use were not clinically significant.31 Two studies measuring pain found no significant difference when comparing the DAA and PA; however, both noted a trend of lower pain levels that bordered significance up to 3 months post-op.16,32 Additionally, two studies measured pain via serum concentrations of muscle breakdown products and acute-phase reactants. In these studies, serum kinase and C-reactive protein levels were elevated in patients with PA compared to DAA, which was interpreted as an indicator of inflammation that would translate to greater pain.33,34

Functional Outcomes

Studies examining functional outcomes between the DAA and PA reported that the DAA was associated with earlier improvement in hip function. Many studies investigating functional outcomes have found similar results, evidenced by either significantly improved hip function or a trend of greater improvement, just falling short of significance, in DAA compared to PA.15–17,23,31,32,35,36 The point of contention in the literature is how long the difference in function remains. The most common time point demonstrating significance is 4-6 weeks, beyond which the PA group patients begin to show similar functional outcomes to the DAA patients.23,26,30–32,36,37 Some papers demonstrated significance among DAA and PA groups using the Harris Hip Score (HHS). However, other studies found no significant differences in HHS scores but saw that the DAA group had fewer patients using ambulatory devices by the specified time point.

In contrast, two studies concluded that the functional advantages of DAA did not extend past 2-3 weeks.27,38 Alternatively, two studies found that functional outcomes, as measured by the HHS score, were extended up to 3 months after surgery.17,34 Quinzi et al. used a patient self-reporting system where patients could grade their own perceived physical function. Interestingly, this method showed benefits in functional outcomes as seen in DAA versus PA extended up to one year postoperatively.39

Complications

There is no clear consensus when examining the complication rates between DAA and PA; however, some studies suggest that DAA has a slightly higher overall rate of complications.32,40 One study investigating major surgical complications within one year after surgery found a slightly increased rate (1 versus 2 %) in the DAA group.40 Regarding the specific complications, the PA has been associated with a greater risk of dislocation due to the posterior capsule’s role as a static stabilizer,15,33,41 while the DAA has been shown to have a greater risk of intra-operative fractures and LCFN injury.37 Interestingly, more complications were observed earlier in a surgeon’s training with the DAA, which significantly decreased with experience. This phenomenon, termed the “learning curve,” on average, lasts approximately 100 cases and has been attributed to the DAA being technically challenging, leading to increased complications in surgeons inexperienced with the technique.33 Studies aimed at characterizing the learning curve showed a significant increase in complications in the first 30 cases of experience, gradually decreasing and normalizing at 100 cases.30,42 One study examined complication rates between a surgeon with a year’s worth of expertise versus six surgeons learning the DAA. The results indicated that experienced surgeons had a significantly lower complication rate than novice surgeons, with trainee surgeons improving their complication rates as they gained more experience with the DAA.43

Furthermore, another study comparing the complication rates of two surgeons with significant experience in both techniques found no significant difference in complication rates when these surgeons performed either the PA or DAA.16 Thus, the increase in complication rates seen with the DAA may be largely attributable to the learning curve phenomenon. Additionally, the DAA has been consistently associated with a decrease in the length of stay, a significant factor in reducing complications such as nosocomial infections.17,30,33

DAA Versus the Lateral Approaches (LA)

Most recent literature comparing THA approaches focuses on the DAA versus the PA; however, there is still interest in comparing the DAA versus the ALA and DLA. Studies investigated pain, functional outcomes, and complications. The studies comparing the DAA versus LA trend towards the DAA being associated with early decreased postoperative pain, better early functional outcomes, and slightly increased rates of complications.

Pain Outcomes

Two studies measuring pain found significantly reduced pain within three days post-op when comparing the DAA to the LA. These studies also measured narcotic use and found significant differences between the DAA and LA. Brismar et al. showed a reduction in morphine use (140mg in DAA vs. 175mg in DLA) over the initial three days after surgery in the DAA group.35 Another study calculated a standardized oral morphine equivalent daily dose (oMEDD), which showed an average of 63.05mg for DAA versus 79.81mg for the LA.29 Furthermore, there was a significant difference in the duration of opioid use among DAA patients (DAA averaging 12 days vs PA averaging 14 days).35 When measuring pain via VAS, one study found that DAA showed statistically, but not clinically, improved pain within two weeks post-op when compared to pain in the DLA group.31 Inflammatory cytokines were used as a measure of surgical trauma and pain between the DAA and LA. They found increased interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, and tissue necrotizing factor (TNF-α) in the LA relative to the DAA during the initial four days after surgery. However, these findings did not translate to a clinical difference in pain.44

Functional Outcomes

Restrepo et al. compared functional outcomes between the DL and DAA approach and found a significantly improved function with DAA when measured at six weeks, six months, and 12 months.45 The results showing the benefits of DAA at 6 and 12 months have not been replicated. However, more recent literature has consistently replicated improved functional outcomes in the DAA group relative to the LA at 6-8 weeks.15,23,31,32,35 Alternatively, another study used both HHS and imaging to measure functional outcomes between the LA and DAA. They concluded that patients in the lateral approach group had more significant fat atrophy in their gluteus muscles and increased TFL thickness; however, no significant difference was found in HHS when measured at 3 and 12 months.44

Complications

Much like the comparison of DAA and PA, when comparing the complications of DAA versus LA, evidence suggests that DAA has a higher complication rate.40 However, the specific complications associated with the DAA and LA differ. The LA is associated with a greater rate of altered gait mechanics, specifically, a Trendelenburg gait.15,23,33 The LA involves tenotomy of the abductor muscles to gain access to the hip capsule, contributing to abductor muscle insufficiency and resultant Trendelenburg gait.15 Tissue infections and dislocations were complications commonly mentioned when comparing the LA to the DAA.

The literature presents mixed findings, with some studies reporting an increase in infections and dislocations associated with the DAA, while others report no significant difference.35,40,41 As previously discussed, the significant learning curve associated with the DAA may contribute to the mixed findings regarding complications. One study showed no significant difference in the relative risk between the LA and DAA, even with slightly increased complications in DAA.32

PA Versus the Lateral Approaches

Currently, there is minimal recent research comparing the PA and LA. Of these papers measuring postoperative pain, the results are mixed, with some finding no difference in pain while others found an increase in pain after surgery compared to the DL.46–48 However, there were significant delays in function outcomes up to 12 months in the LA compared to the PA.46–48 Many of these papers consist of small patient cohorts of up to 140 patients. Furthermore, some of the papers were conducted in the Eastern hemisphere with different postoperative care norms compared to Western patient populations.47 The lack of research in this area necessitates further investigation as the PA and DL are the two most commonly used approaches in the world.14

Discussion

Studies comparing the THA surgical approaches often conclude there is no clearly superior approach, which is reflected in the current American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) guidelines for exposure approaches in THA. Without clear evidence to guide the selection of an approach for a total hip arthroplasty (THA), utilizing the knowledge of the pros and cons of each approach in conjunction with the individual patient’s history can help determine which one is better suited for a given individual. In the case of the DAA, evidence suggesting that the DAA may provide the benefit of early recovery is best suited for patients who are employed, as it facilitates a quicker return to driving and work.49 Additionally, utilizing aspects of the medical and social history may provide insight for the use of the DAA. For example, some studies conclude risk factors for greater THA postop pain are multiple medical or psychiatric comorbidities.50 Additionally, another consideration could be taken for those with chronic preop opioid use, as it has been shown that chronic opioid use can lead to hyperalgesia.51 With evidence suggesting the DAA may provide the benefit of decreased postop pain, the DAA may be the best approach for these patient populations. Alternatively, the DAA is associated with a greater incidence of surgical site infections, so patients at an elevated risk of infections may be better candidates for any of the PA, DLA, or ALA. Specifically, the DAA is associated with a greater infection risk in individuals with an elevated BMI; however, scoring systems such as the American College of Surgeons (ACS) surgical risk calculator can be used to stratify those with a higher-than-average surgical site infection risk, allowing for the avoidance of the DAA in these patients.52 Furthermore, those with risk factors for postop hip dislocations such as previous spine surgery, neurological disease, psychiatric disease, or greater ASA score are likely better candidates for the DAA, DLA, or ALA rather than PA may.53 The DLA and ALA both have the risk of gait alteration due to violation of the abductor mechanism, which can be minimized with partial tenotomy with tendon repair. However, these approaches may want to be avoided in patients with multiple risk factors for poor wound healing that may increase the risk of tendon repair failure, such as those with diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, obesity, alcoholism, preop malnutrition, or chronic smokers.54

Conclusion

While there are no clear guidelines to help select the best approach for THA, that decision should be made by analyzing the various contributing factors. These include the surgeon’s comfort level with each approach, evaluating patient risk factors and social history such as employment status, and utilizing shared decision-making after discussing the risks and benefits of each approach. The improved early outcomes associated with DAA appeal to both patients and surgeons; however, this must be carefully weighed with the existing learning curve. Most literature comparing approaches consists of low-power studies that focus specifically on short-term outcomes, with most studies measuring outcomes up to 12 months postoperatively. Greater powered studies investigating potential differences in long-term outcomes between the approaches are needed. The decision to use one approach over another is multifactorial and will vary on a patient-by-patient basis, as well as with experience in the various techniques.

Declaration of conflict of interest

- Ahmed Siddiqi: Consultant – Stryker, Consultant - United Orthopedics

Declaration of funding

The authors received NO financial support for the preparation, research, authorship, and publication of this manuscript.

Declaration of ethical approval for study

Thomas Jefferson University does not require ethical approach for Current Review papers.

Declaration of informed consent

There is no information (names, initials, hospital identification numbers, or photographs) in the submitted manuscript that can be used to identify patients.