INTRODUCTION

The implications of artificial intelligence (AI), and in particular Chat Generative Pretrained Transformer (ChatGPT), given its widespread availability, in academic writing, has been the subject of increasing concern amongst educators. Debates on potential student reliance on AI and the impact on education in general and scientific writing in particular, without clear guidelines on how to approach these challenges, continue. Although AI has been given credit for academic prowess, performing well on board and bar exams, in education, students who rely on AI without regard to process and knowledge acquisition directly from reputable sources have risks. Deeper understanding and comprehension of the subject matter often develop through a process of seeking, vetting, and assimilating knowledge from various sources. The additional risk of falling victim to plagiarism in the production of original work compromises educational integrity and authenticity.1 In collaborative research, the over-reliance on AI poses a uniquely challenging threat to compromising the integrity of scientific writing and findings, with the associated risk for compromising personal, professional, and institutional reputation by publishing plagiarized or inaccurate AI-generated content.

This paper will present a case study of a ChatGPT-generated “scientific paper” that cleared plagiarism detection but failed an AI detection tool. The goal of this paper is to highlight the risk of AI tools like ChatGPT in the scientific process and present a strategy for research mentors and senior investigators to avoid compromising their research and reputation with AI-plagiarized content.

HOW DOES CHATGPT WORK?

AI draws on information available online and has been pretrained in “learning language models” and “natural language processing” to create seemingly meaningful responses to queries from users.2 ChatGPT is an AI tool, created by OpenAI, that utilizes “generative AI” models that are capable of creating new data based on patterns from existing available data. Generative AI can create content across many areas, including data, images, music, and other forms. ChatGPT in particular uses an advanced generative AI model with deep learning techniques and neural networks to analyze data and then create content that mimics human style.3 Moreover, ChatGPT is being actively updated and advanced. At the time of this writing, the current ChatGPT system available is GPT-4. As such, ChatGPT can and will have an impact on all areas that intersect online with human life.

For scientific inquiries, there are several challenging data and ethical considerations with ChatGPT. First, from a data acquisition and processing perspective, ChatGPT does not have access to subscription-based content and relies primarily on open-access data. Therefore, it has limited access to all potentially available scientific data. Second, from an ethical consideration, plagiarism is a concern. Content produced by ChatGPT is assimilated from various sources or created de novo based on assumptions made by the platform. Use of this content without proper attribution could qualify as plagiarism. We will discuss both issues further in this paper.

CASE STUDY

A unique case of a rare dermatologic finding presented to the co-author (ENI) was submitted for publication as a case report to share these findings in the medical literature. After medical students gathered relevant data from the patient, a pre-medical student requested to write the manuscript and subsequently queried ChatGPT to generate a case report.

Although an initial read of the draft manuscript was coherent, the inconsistencies with the current literature regarding the assertion and conclusions drawn, as well as suspicious references cited, drew deeper scrutiny. Although supporting references were offered by the “manuscript”, unexpected details provided were not consistent with the current understanding of the condition in the current medical literature. Although properly formatted, a review of the references listed by cross-checking PubMed and Google Scholar revealed that some were mis-referenced or non-existent. [Table 1]

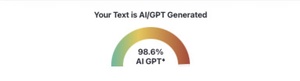

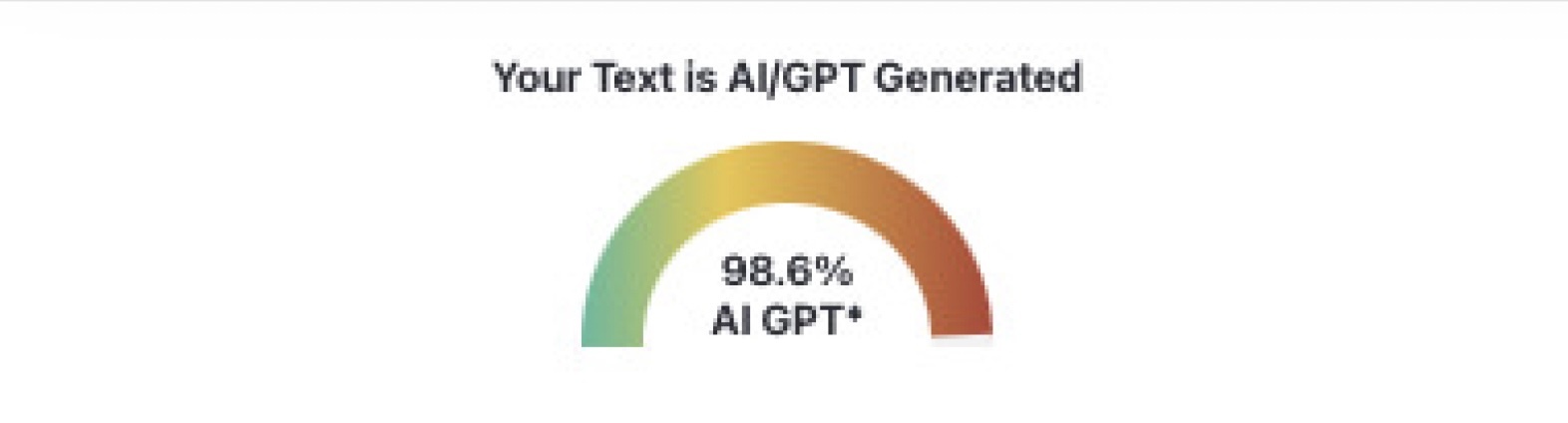

The manuscript was then checked through an online plagiarism detection tool, PapersOwl [Figure 1], as well as an online AI-detection tool, ZeroGPT [Figure 2].

Although the online plagiarism detection tool failed to detect suspicious findings for plagiarism, the AI-detection tool determined the paper to be entirely AI-generated.

Reviewing this case raised several questions that have not been adequately addressed in the literature regarding the use of AI in scientific writing in the context of research oversight and mentorship. Amongst these concerns are what constitutes plagiarism, how to spot a fake, how AI generates its own references, and tools for educators to navigate AI use by students.

PLAGIARISM

The Merriam-Webster dictionary online defines “plagiarism” as taking credit for a work without proper attribution or crediting of the source.4 AI-generated content and its intersection with plagiarism is ambiguous, as AI and tools like ChatGPT draw their content from current available online information as well as user input to generate their own content based on assumptions without necessarily sourcing the original work, and often creating references when they do not exist. The result is information that is an amalgamation of online content, along with potentially grammatically correct gibberish and falsehoods. Scientific writing is traditionally predicated on thoughtful and deliberate sourcing of information while qualifying its credibility and attributing the source information to the authors and the publication platform. This allows the readers of a scientific paper to assess for themselves the credibility of the scientific findings and the integrity of the sources cited. Although AI tools are here to stay and can potentially serve a role in literature review and writing support, the unbridled use of AI-generated content risks producing inaccurate information with false or missing attributions of the source material. As such, AI-generated content, at best, is accurate but at worst is incorrect, and still not properly attributed, can be considered a form of AI-plagiarism.

HOW TO SPOT AI-PLAGIARISM

It is understood that the world of AI is fast evolving and that the ability for mentors to screen students’ work for AI use will come with increasing challenges. However, it should not be forgotten by educators and research mentors that educational pursuit intends to develop personal subject matter expertise, drawing on all available data - not just online content, to develop original writing to transmit novel ideas and confirm or advance knowledge. The key for mentors in evaluating student research submissions, and to avoid risking personal and professional reputational harm, is to understand patterns noted in AI content and strategies that will protect the academic integrity of scientific work. Specifically, we advocate for senior investigators and research mentors to take the following four steps [Table 1]. when evaluating intended original work produced by their students and/or researchers prior to submission for publication to avoid falling victim to AI-plagiarism: (1) Routine use of AI tools for detecting AI-plagiarism. (2) Scrutinizing conclusions and assertions for scientific validity based on the current best evidence. (3) Checking all references for legitimacy. (4) Noting subtle AI formatting clues.

Use AI Tools for Detection

Prior to the growth of AI tools such as ChatGPT, plagiarism checking services (ie, Grammarly, PapersOwl, Duplichecker) have been available for some time to allow for an efficient review of a manuscript for plagiarism risk, along with a percentage score. Many journals routinely use these services during the intake process of submissions for publication. However, these tools emphasize analysis of the similarity of submitted content relative to published content. These tools are not currently optimally equipped to assess for AI-generated content.

Alongside the development of AI tools to create content has been the creation of AI tools to detect AI-generated text. Essentially, AI can be queried to create content, and AI can also be queried to determine if the content created was AI-generated. A recent study evaluating texts from articles published in JAMA Otolaryngology before and after the introduction of ChatGPT using ZeroGPT.com as an AI text detector found a significant increase in the detection of AI in the writing of abstracts, introduction, and discussion sections of articles after the introduction of ChatGPT.5 Although we would argue for the collaboration of scientific journals and AI experts to create detection tools at the level of pre-publication, challenges exist for academic mentors working with students and researchers in evaluating scientific writing prior to submission for publication. It should also be noted that AI-detecting tools offer an option to “humanize” the text, creating an additional challenge in assessing for AI-generated content.

At this time, we advocate for the routine use of tools to detect AI-generated content (e.g., Turnitin, ZeroGPT, Writer), but also endorse the continued development of these tools as other tools to create AI-generated content continue to advance.

Scrutinize Assertions

AI-generated content is prone to making conclusions and assertions based on assumptions it makes from available online content. Research mentors should have the advantage of historical knowledge of the subject matter in question, an understanding of the subject matter’s controversies and knowledge gaps that persist, and humility in the conclusions that can or cannot be made relative to the subject matter’s best available evidence.

In the case study presented here, this paper’s senior author (ENI) determined a patient’s findings to be worthy of publication based on the novel finding of a genetic mutation known to trigger cutaneous findings in homozygote children that may trigger similar cutaneous findings in adult heterozygote carriers, hence warranting the production of a case report. When the student writer used AI to help write the manuscript, ChatGPT decided to create its own conclusion that the patient’s cutaneous findings were drug-induced and produced a reference to support its decision. However, no source is found in the literature to support this conclusion or corroborate this claim.

AI-generated content, although robust in quantity and confidence, lacks the level of insight a research mentor possesses. That insight, or human factor, should be leveraged by mentors when strong conclusions and assertions are made in a manuscript that are not consistent with the current best evidence, and should trigger the mentor to challenge the source of the material for potential AI-generated content.

Check References

Perhaps the most objective way to assess for AI-generated content in scientific writing is to assess the validity and accuracy of its cited references. It is well-documented that ChatGPT can create verifiably false references.6 In the case study presented here, ChatGPT provided a list of “references” including digital object identifier (DOI) numbers. Following the DOI links led to articles that were completely unrelated to the topic. Moreover, checking the specific journal volume, issue, and page numbers revealed completely unrelated articles published in these sources, if they existed at all. [Table 2]

It would appear as though AI used references found in open-access content to create references that appeared plausible based on authors, titles, and journals; however, these references did not actually exist. Although access to many journal articles often requires user agreements or subscription rights, all references can readily be cross-referenced in PubMed or Google Scholar, and we would advocate for routine cross-referencing. Any pattern of inconsistency should immediately raise suspicion for AI-generated content.

Formatting Clues

Before even diving into the details, assertions, and conclusions found within the text of a manuscript, it is useful for the mentor to take a high-level or superficial assessment of the paper’s formatting. AI tools that create content have several “tells”. The papers or content they generate appear to default formatting with bold headings, colons following section headings, and the lack of use of general formatting details, such as indentation to start paragraphs and double spacing. Although not routinely seen in papers generated by AI, emails generated by AI appear to make use of bold fonts to highlight key features requested by the query for emphasis. Aside from the reference disparities discussed above, AI-generated papers do not consistently employ references for various facts noted within the body of the paper, as is customary practice in scientific writing. It is important to note that these discrepancies can be self-adjusted, or additional AI queries can be made to request changes to improve formatting. However, a quick high-level review of a paper can reveal these subtle details and raise suspicions about AI-generated content.

CONCLUSION

In research, the increasing over-reliance on AI to generate scientific content poses a burgeoning challenge for research mentors overseeing writing by students and/or junior investigators. At risk are both the scientific findings of the study and the reputation of the mentor, subordinate researchers, and, by extension, their institution. A deliberate strategy to assess potential AI-plagiarism should be employed by research mentors to decrease this risk, including: (1) Routine use of AI tools for detecting AI-plagiarism. (2) Scrutinizing conclusions and assertions for scientific validity based on the current best evidence. (3) Checking all references for legitimacy. (4) Noting subtle AI formatting clues. However, beyond the mentors policing the work of their subordinates, we would strongly advocate for institutional forces to work with AI technology generators to create best practices and/or tools to better avoid AI-plagiarism and its subsequent potential compromise of the scientific process. Importantly, institutions need to create policies to set guidelines for AI use and specifically label AI plagiarism as grounds for disciplinary action.

Declaration of conflict of interest

The authors do NOT have any potential conflicts of interest for this manuscript.

Declaration of funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Declaration of ethical approval for study

N/A

Declaration of informed consent

N/A